ECON 730: Causal Inference with Panel Data

Lecture 1: Course Overview and Introduction

Emory University

Spring 2026

Welcome to Econ 730

About Your Instructor

Pedro H. C. Sant’Anna

- Research focus: Causal inference, Difference-in-Differences, Applied Econometrics

- Office Hours: Tuesdays 1:00–2:00 PM (or by appointment)

- Contact: pedro.santanna@emory.edu

- Course website: psantanna.com/Econ730

- We will create a Slack channel for class communication

Teaching Assistant: Marcelo Ortiz-Villavicencio

My commitment to you: I want every student to succeed. This course will be challenging, and will require hard work. But I will support you every step of the way.

My Work Philosophy and What I Value

Hard work and dedication: I value putting in the hours and sustained effort to master difficult material

Presentation and storytelling: Clear communication of ideas is just as important as technical rigor

Coding skills: Modern applied econometrics should be reproducible—most papers should be accompanied by software packages

Intuition and connections: Ability to see relationships between topics and build conceptual understanding

First-principles thinking: Always understand the fundamental logic before applying methods

Mathematics as a tool: Math ensures correctness, but simplicity is a virtue—elegance over complexity

What this means for you: This course will be demanding and labor-intensive, but it will build grit and bring you to the research frontier.

Course Scope: What we will do

- Master the handling of potential outcomes in panel data settings

- Discuss panel experiments and randomized rollouts

- Difference-in-Differences and event studies

- Single treatment timing

- Staggered adoption

- Continuous and multi-valued treatments

- Triple differences

- Synthetic controls and matrix completion

- Panel IV, factor models, and surrogate analysis

Learning Objectives

By the end of this course, you will be able to:

Understand how longitudinal/panel data allow you to answer richer causal questions with less stringent assumptions

Understand the strengths and limitations of different causal panel data methods

Implement these methods in practice (using R, Python, Stata, or Julia)

Critically evaluate research papers that use these tools

Course Structure: 14 Weeks Ahead

| Week | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Causal Panel Data: Mastering Potential Outcomes |

| 2 | Randomizing Treatment Sequences |

| 3 | Introduction to Difference-in-Differences |

| 4 | Incorporating Covariates into DiD |

| 5 | Uncertainty + Better Understanding Parallel Trends |

| 6 | Event Studies and DiD with Multiple Periods |

| 7 | DiD with Variation in Treatment Timing |

| 8 | Triple Differences + DiD with Continuous Treatments |

| 9 | More Complex DiD Designs |

| 10 | Introduction to Synthetic Controls |

| 11 | Advances in Synthetic Controls |

| 12 | Other Causal Panel Data Methods |

| 13 | Surrogate Analysis and Long-Term Effects |

| 14 | Replication Presentations |

Course Evaluation

| Component | Weight | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| Class Participation & Contribution | 10% | Ongoing |

| Problem Set 1 | 15% | Week 4 |

| Problem Set 2 | 15% | Week 8 |

| Problem Set 3 | 15% | Week 12 |

| Short Reports & Presentation | 25% | Weekly |

| Replication Project | 20% | Week 14 |

| Research Proposal (Optional) | 0% | – |

Note on Workload: This is an ambitious course. Expect substantial time on problem sets (theory, simulations, empirical work) and weekly readings.

Class Participation (10%)

Weekly Memo:

- Submit a brief note (1–2 paragraphs) on Canvas each week

- Discuss one required reading for the following week

- Can include: thoughts, questions, or related comments

- Full credit for good-faith effort

Constructive Engagement:

- Participate actively in class discussions

- Ask questions, offer insights, engage with peers

Short Reports & Presentations (25%)

- Starting Week 2, select a topical paper each week

- Write a 2-page report covering:

- Research question(s) addressed

- Why it’s important

- Key challenges

- How data + design + model address challenges

- Contributions and caveats

- Submit every week

Random Presentation Selection:

- 1–2 students randomly selected to present each week

- Presentation is part of your grade

- Once selected twice, you’re removed from the list

Replication Project (20%)

Work in pairs to:

Narrow replication: Reproduce all main results from a published paper

- Many journals now require code/data availability

Broad replication: Extend the analysis

- Use different periods, regions, or methods

- Tackle the same question with fresh perspective

Write a 10-page paper following AEA reproducibility guidelines

Present in Week 14 (10-15 minutes per team)

Research Proposal (Optional)

Strongly Encouraged! Starting your dissertation early is very valuable.

If you choose this path:

- Clearly articulate your research question

- Describe data sources and identification strategies

- Provide reproducible code for preliminary analysis

- Receive feedback from me

This is a great opportunity to develop your thesis research!

If you want me to be on your PhD committee, this is a must-do.

Key Policies

Academic Integrity:

- Emory Honor Code applies to all work

- Collaboration encouraged, but write-ups must be individual (unless group work)

- See Laney Graduate School Handbook

Accessibility:

- Contact Dept. of Accessibility Services for accommodations

- Reach out early—accommodations cannot be retroactive

Diversity & Inclusion:

- All perspectives are valued and respected

- If something in class makes you uncomfortable, please talk to me

Programming and Tools

Statistical Programming:

- Primary language: R

- You may use Python, Stata, or Julia

- My assistance with alternative languages is more limited

AI Tools:

- I encourage exploring AI tools (Copilot, Claude Code, ChatGPT, Gemini, etc.)

- They can enhance productivity—but you must verify all code!

- AI tools supplement your skills, they don’t replace them

Reproducibility:

- Write well-documented, clear code

- Follow best practices for reproducible research

Why Causal Panel Data?

Empirical Appeal of Panel Data

Many of the most important causal questions involve time:

Do states that expanded Medicaid in a given year have better mortality rates than states that have not yet expanded?

What is the effect of minimum wage increases on employment when different states adopt at different times?

How does continuous variation in fracking intensity affect local employment when different areas start at different times?

What is the causal effect of hospitalization on out-of-pocket medical spending in subsequent months?

What would California’s tobacco consumption have been in the absence of Proposition 99?

Does procedural justice training reduce police complaints and use of force when districts are trained at different times?

The Rising Prevalence of Causal Panel Data Methods

The following figures are based on Goldsmith-Pinkham (2024), which tracks the use of different empirical methods in economics by analyzing NBER working papers and top economics journals (AER, QJE, JPE, AEJ:Applied, AEJ:Policy).

- Data and replication code available at: paulgp.com/econlit-pipeline

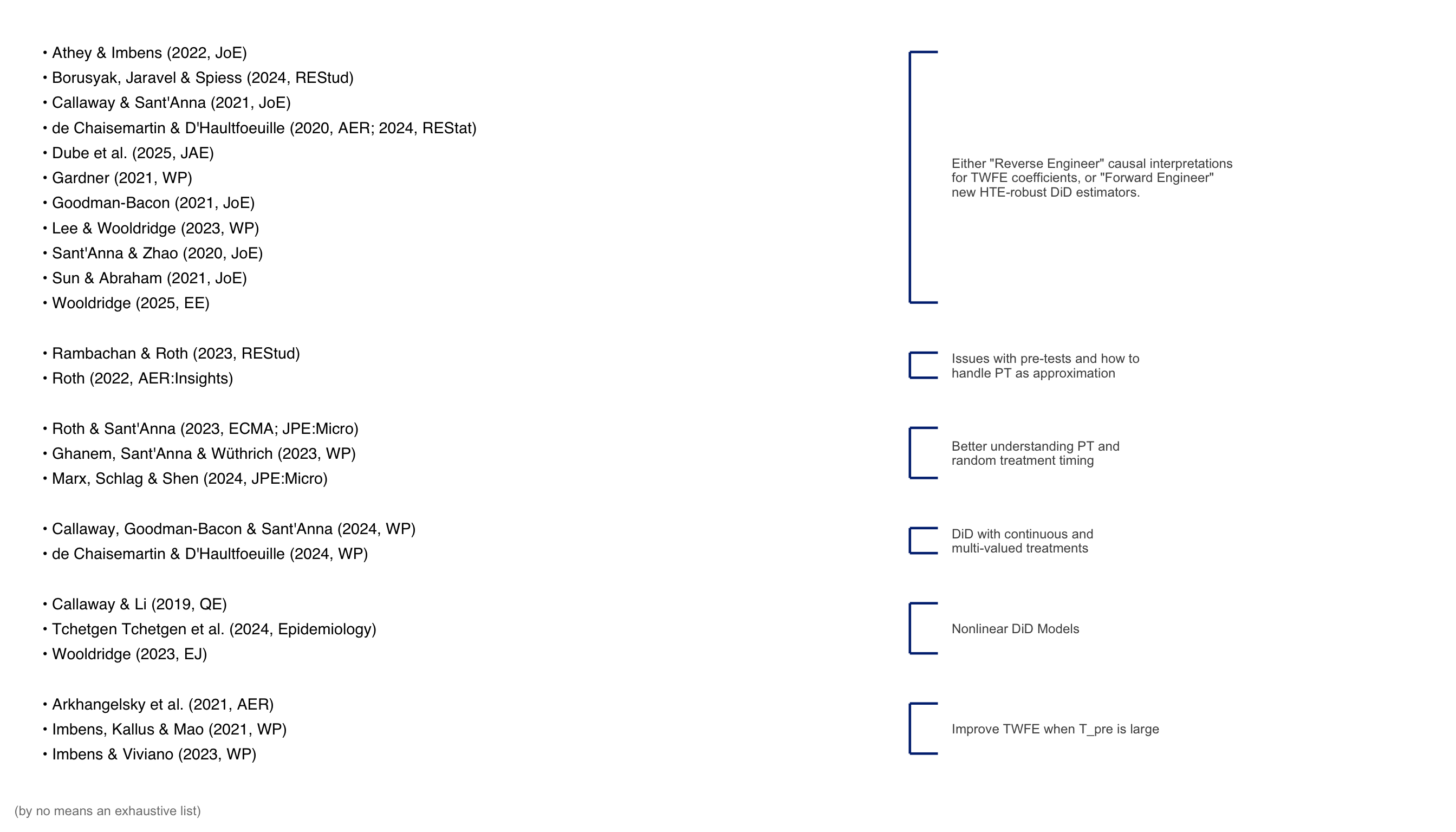

Recent Methodological Advances in DiD

Empirical Applications

Empirical Applications: A Preview

This course covers modern causal panel data methods. The next slides highlight influential empirical applications that showcase these techniques.

- Randomized Treatment Timing

- Difference-in-Differences with Single Treatment Date

- Staggered Difference-in-Differences

- Synthetic Controls

- Difference-in-Differences with Continuous Treatment

- Panel Instrumental Variables

Each method addresses different research designs and identification challenges

Randomized Treatment Timing: Procedural Justice Training

Application: Wood, Tyler, and Papachristos (2020)

Research Question:

- Does procedural justice training reduce police use of force and complaints?

Setting and Design:

- Chicago Police Department, 2011–2016

- 8,480 officers trained across 49 months in a staggered rollout

- Treatment timing was randomized across training cohorts

- Once trained, officers remain in the “treated” state

Procedural Justice Training: Results

Key Findings:

- Original analysis found large reductions in complaints and use of force

- Re-analysis by Wood et al. (2020) using modern staggered DiD methods showed smaller effects—detecting an error in the original data analysis

- Highlights importance of robust estimation under treatment effect heterogeneity

Methodological Relevance:

- Staggered rollout with randomized timing enables efficient estimation

- Roth and Sant’Anna (2023a) show how to exploit randomization for sharper inference

- Confidence intervals can be up to 8× shorter than standard approaches

Classic DiD: Minimum Wage and Employment

Application: Card and Krueger (1994)

Research Question:

- Does raising the minimum wage reduce employment in the fast-food industry?

Setting and Design:

- New Jersey raised minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05 on April 1, 1992

- Pennsylvania kept minimum wage at $4.25 (control group)

- Survey of 410 fast-food restaurants before and after the change

- Classic 2×2 difference-in-differences design

Card & Krueger: Results and Impact

Key Findings:

- No evidence that minimum wage increase reduced employment

- Employment actually increased by 13% in New Jersey relative to Pennsylvania

- Challenged the standard competitive labor market prediction

Why This Paper Matters:

- Sparked renewed interest in monopsony models of labor markets

- Pioneered the “natural experiment” approach in labor economics

- Demonstrated power of quasi-experimental methods

- One of the most influential papers in labor economics

Staggered DiD: Bank Deregulation and Economic Growth

Application: Jayaratne and Strahan (1996)

Research Question:

- Does bank branch deregulation affect state economic growth?

Setting and Design:

- U.S. states removed restrictions on intrastate bank branching at different times

- Staggered adoption across states from 1972–1991

- Compare economic growth before and after deregulation

- Control states: those that have not yet deregulated

Jayaratne & Strahan: Results

Key Findings:

- States that deregulated experienced faster economic growth

- Per capita income growth increased by 0.51–1.19 percentage points annually

- Effects driven by improved bank lending quality, not quantity

Why This Paper Matters:

- Classic staggered DiD design exploiting policy variation across states

- Demonstrates finance-growth nexus using quasi-experimental variation

- Early influential example of using staggered adoption for identification

Staggered DiD: Medicaid Expansions

Applications: Currie and Gruber (1996); Sommers, Baicker, and Epstein (2012); Miller, Johnson, and Wherry (2021)

Research Question:

- Do Medicaid expansions improve health outcomes?

A Long History of Staggered Adoption:

- 1980s–90s: States expanded Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women and children at different times

- 2000s: Some states expanded adult coverage before ACA

- 2014+: ACA allowed further state expansions

Medicaid Expansions: Key Findings

Currie & Gruber (1996, JPE):

- Medicaid expansions for pregnant women reduced infant mortality

- Staggered state adoption provides identification

Sommers, Baicker & Epstein (2012, NEJM):

- Pre-ACA state expansions reduced mortality by 6.1% among adults

Miller, Johnson & Wherry (2021, QJE):

- ACA Medicaid expansion reduced mortality by 9.4%

- Effects grow over time; driven by disease-related deaths

Staggered DiD: Unilateral Divorce Laws

Applications: Wolfers (2006); Goodman-Bacon (2021)

Research Question:

- Do unilateral divorce laws increase divorce rates?

Setting and Design:

- U.S. states adopted unilateral (“no-fault”) divorce laws at different times

- Staggered adoption from 1969–1985

- Compare divorce rates before and after law changes

Divorce Laws: Methodological Lessons

Key Findings (Wolfers 2006):

- Initial spike in divorce rates after adoption

- Effects fade over time—long-run effect is smaller or zero

- Dynamic treatment effects matter: timing of measurement is crucial

Methodological Insight (Goodman-Bacon 2021):

- Uses divorce laws as primary example for TWFE decomposition

- Shows TWFE coefficient is weighted average of many 2×2 DiD comparisons

- Some comparisons use already-treated units as controls (problematic!)

- Highlights importance of heterogeneous treatment effects over time

Synthetic Controls: Economic Costs of Terrorism

Application: Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003)

Research Question:

- What are the economic costs of the terrorist conflict in the Basque Country?

Setting and Design:

- ETA terrorism began in the late 1960s in the Basque region of Spain

- Compare Basque Country to a “synthetic” control region

- Synthetic control = weighted average of other Spanish regions

- Weights chosen to match pre-terrorism economic characteristics

Abadie & Gardeazabal: Results

Key Findings:

- Per capita GDP in Basque Country declined ~10 percentage points relative to synthetic control

- Gap widened during periods of increased terrorist activity

- 1998–1999 truce: stocks of Basque firms showed positive performance; reversed when truce ended

Why This Paper Matters:

- Introduced the synthetic control method to economics

- Provides transparent, data-driven approach to comparative case studies

- Foundation for a vast methodological literature

Synthetic Controls: Decriminalizing Indoor Prostitution

Application: Cunningham and Shah (2018)

Research Question:

- How does decriminalizing indoor prostitution affect sexual violence and public health?

Setting and Design:

- Rhode Island accidentally decriminalized indoor prostitution in 2003

- Court ruling created an unexpected natural experiment

- Construct synthetic Rhode Island from other states (Iowa, Idaho, South Dakota)

- Compare rape offenses and gonorrhea rates before and after

Cunningham & Shah: Results

Key Findings:

- Decriminalization increased the size of the indoor sex market

- Forcible rape offenses fell by 31% (824 fewer reported rapes, 2004–2009)

- Female gonorrhea incidence fell by 39% (1,035 fewer cases)

- Indoor markets may be safer for both sex workers and clients

Methodological Notes:

- Discuss synthetic control and difference-in-differences approaches

- Addresses unexpected policy change—hard to argue for reverse causality

- Careful attention to pre-trends and placebo tests

DiD with Continuous Treatment: Medicare and Hospital Inputs

Application: Acemoglu and Finkelstein (2008)

Research Question:

- How do regulatory changes affect input choices and technology adoption in hospitals?

Setting and Design:

- Medicare introduced Prospective Payment System (PPS) in 1983

- Before PPS: hospitals were reimbursed for a share of labor and capital costs proportional to their Medicare patient share

- After PPS: labor subsidy eliminated, capital subsidy unchanged

- Treatment intensity varies continuously with hospital’s Medicare share

Acemoglu & Finkelstein: Results

Key Findings:

- Hospitals with higher Medicare share increased capital-labor ratios substantially

- PPS encouraged adoption of new medical technologies

- Skill composition of hospital workforce increased (capital-skill complementarity)

Modern DiD Perspective:

- Original paper used two-way fixed effects (TWFE) estimator

- Re-analysis with modern continuous DiD methods (Callaway, Goodman-Bacon, and Sant’Anna 2024) finds effects ~50% larger than TWFE estimate

- Highlights weighting issues in conventional approaches

Panel IV: Compulsory Schooling and Returns to Education

Application: Oreopoulos (2006)

Research Question:

- What are the returns to education?

Setting and Design:

- UK raised minimum school-leaving age from 14 to 15 in 1947

- Sharp policy change creates strong first stage for IV

- Compare cohorts just before vs. just after the law change

- Uses panel of repeated cross-sections across birth cohorts

Key Findings:

- Compulsory schooling law increased education by ~0.5 years

- Returns to education: 10–14% per year

- Strong first stage avoids weak instrument problems of quarter-of-birth designs

Instrumented DiD: The Americans with Disabilities Act

Application: Acemoglu and Angrist (2001)

Research Question:

- Did the ADA improve employment outcomes for disabled workers?

Setting and Design:

- ADA took effect in 1992 (firms ≥25 employees) and 1994 (firms ≥15)

- DiD: compare disabled vs. non-disabled workers, before vs. after ADA

- Exploit firm size thresholds and state variation in enforcement

Key Findings:

- Employment of disabled workers declined after ADA

- Effects larger in medium-size firms and high-enforcement states

- Accommodation costs may have discouraged hiring

Treatment Switching: Democracy and Economic Growth

Application: Acemoglu et al. (2019)

Research Question:

- Does democracy cause economic growth?

Setting and Design:

- Panel of 175 countries from 1960–2010

- Countries transition in and out of democracy over time

- 122 democratizations and 71 reversals (treatment switches on and off)

- Dynamic panel with country and year fixed effects

Key feature: Unlike staggered adoption, treatment can turn off—countries can democratize and later revert to autocracy

Democracy and Growth: Results

Key Findings (Acemoglu et al. 2019):

- Democratization increases GDP per capita by ~20% in the long run

- Effects grow over time (dynamic treatment effects)

- Both democratizations and reversals yield consistent results

Methodological Challenges (Chiu et al. 2025):

- Treatment reversals complicate standard staggered DiD estimators

- Many HTE-robust estimators assume absorbing treatment (no reversal), but this alone does not address treatment carryovers

- Need estimators that allow treatment to switch on and off

Surrogate Analysis: Estimating Long-Term Effects

Applications: Athey et al. (2025); Chen and Ritzwoller (2023)

The Problem:

- Long-term outcomes (e.g., lifetime earnings) are observed with long delays

- Experiments may end before long-term effects can be measured

- How can we estimate long-term treatment effects using short-term data?

The Solution: Surrogate Index

- Combine multiple short-term outcomes into a “surrogate index”

- Predicted value of long-term outcome given short-term proxies

- Under surrogacy assumptions, treatment effect on index = long-term effect

Surrogate Analysis: Methods and Applications

Athey, Chetty, Imbens & Kang (2025, REStud):

- Develop surrogate index methodology

- Application: California job training experiment (GAIN)

- Use short-term employment to predict 9-year employment effects

- Characterize bias from violations of surrogacy assumption

Chen & Ritzwoller (JoE 2023):

- Semiparametric efficiency bounds for surrogate models

- Double/debiased ML estimators for long-term effects

- Application: Poverty alleviation program evaluation

Summary: Empirical Applications Across Methods

| Method | Application | Paper |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized Timing | Police Training | Wood, Tyler, and Papachristos (2020) |

| Classic DiD (2×2) | Minimum Wage (NJ/PA) | Card and Krueger (1994) |

| Staggered DiD | Bank Deregulation | Jayaratne and Strahan (1996) |

| Staggered DiD | Medicaid Expansions | Currie and Gruber (1996); Miller, Johnson, and Wherry (2021) |

| Staggered DiD | Divorce Laws | Wolfers (2006); Goodman-Bacon (2021) |

| Synthetic Control | Basque Terrorism | Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003) |

| Synthetic Control | Indoor Prostitution | Cunningham and Shah (2018) |

| Continuous Treatment | Medicare PPS Reform | Acemoglu and Finkelstein (2008) |

| Panel IV | Compulsory Schooling (UK) | Oreopoulos (2006) |

| Instrumented DiD | Americans with Disabilities Act | Acemoglu and Angrist (2001) |

| Treatment Switching | Democracy & Growth | Acemoglu et al. (2019) |

| Surrogate Analysis | Long-Term Effects | Athey et al. (2025); Chen and Ritzwoller (2023) |

Course Roadmap

Methods We’ll Cover

Randomized Experiments (Week 2)

- Sequential randomization, staggered rollouts

Difference-in-Differences (Weeks 3–9)

- Basic DiD, covariates, event studies, staggered timing

- Triple differences, continuous treatments, fuzzy DiD

Synthetic Controls (Weeks 10–11)

- Classical synthetic control, matrix completion, factor models

Other Methods (Weeks 12–13)

- Lagged dependent variables, bridge functions, marginal structural models

- Surrogate analysis for long-term effects

Next Class: Potential Outcomes in Panel Data

Topics:

- Potential outcomes framework with time dimension

- Treatment sequences and treatment histories

- Staggered adoption and treatment switching

- Parameters of interest: ATT, dynamic effects, event studies

- Mapping research questions to causal parameters

- No-carryover and limited carryover assumptions

Preview Readings:

Office Hours and Questions

How to Reach Me:

- Office Hours: Tuesdays 1:00–2:00 PM

- Email: pedro.santanna@emory.edu

Teaching Assistant:

- Marcelo Ortiz-Villavicencio (marcelo.ortiz@emory.edu)

Questions?

Let’s get started!

See you on Thursday.

References

ECON 730 | Causal Panel Data | Pedro H. C. Sant’Anna