ECON 730: Causal Inference with Panel Data

Lecture 2: Potential Outcomes and Causal Parameters

Emory University

Spring 2026

Preliminaries

Motivating What-If Questions

- In this course, we are interested in asking and answering “What-if” types of questions.

- What is the causal effect expanding Medicaid in a given year on mortality rates compared to not expanding at all? What about compared to expanding 5 years later?

- What is the causal effect of minimum wage increases on employment? Do these effects vary over time? Do these effects vary across states that raised minimum wage in different years?

- Does procedural justice training reduce police complaints and use of force? Do these effects vary across years since training? Do these effects vary across younger and senior police officers?

- But to answer these questions, we need to have a clear definition of causality.

Causality Definitions from Philosophers

“If a person eats of a particular dish, and dies in consequence, that is, would not have died if he had not eaten it, people would be apt to say that eating of that dish was the source of his death.” – John Stuart Mill (19th-century moral philosopher and economist)

“Causation is something that makes a difference, and the difference it makes must be a difference from what would have happened without it.” – David Lewis (20th-century philosopher)

Causal Inference Is Hard

Mill’s counterfactuals were immensely valuable for providing a clear and intuitively valid definition of causality.

But it also made it clear that causality is a tricky business!

If I have to know what would have happened had I not eaten the dish, but I did eat the dish, how would I ever be able to know the causal effect of eating the dish?

The same reasoning applies to all the what-if motivating questions we discussed!

This is a valid concern, but this should not stop us from trying to answer these questions.

Causality Is a Game of Counterfactuals

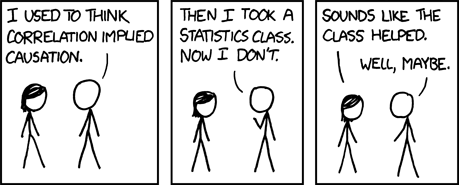

Source: xkcd.com/552

No Causation Without Manipulations

Although this is not a universal point of view, we will adopt the approach popularized by Holland (1986), “No causation without manipulations”.

“Causes are only those things that could, in principle, be treatments in experiment” (Holland 1986).

“Causes are experiences that units undergo and not attributes that they possess” (Holland 2003).

This restricts the problems we work with, or at least forces us to think about the problem from this angle.

Challenges with Causal Inference: Not a Prediction Problem

Causal inference is not a prediction problem but rather a counterfactual problem.

This makes things challenging because:

- Direct use of ML methods is biased for causal effects due to confounding.

- ML aims at minimizing prediction error, not counterfactuals.

- We never observe the true causal effect, which makes model selection trickier.

- We are not only interested in the counterfactual itself but also in quantifying its uncertainty (making inferences).

Some modifications and tricks can be used to bypass several of these.

Key: decompose the problem into predictive and causal parts.

My Approach to Causal Inference

Specify the causal question of interest and map that into a causal target parameter.

Figure out a research design using domain knowledge that can credibly answer the question (This usually involves solving identification problems)

- We usually abstract from sample size considerations here.

- What we want is the “right” data that leverages a “quasi-random” variation in our treatment variable.

State our assumptions, and provide supportive evidence of their credibility in our context.

- Why treatment is “quasi-random”

- For which population you can identify the effects

Pick an estimation and inference method with strong statistical guarantees.

Mapping Questions into Causal Parameters

Examples of Motivating Causal Questions

What is the average treatment effect expanding Medicaid in 2014 on mortality rates compared to not expanding it?

What is the average treatment effect of a minimum wage increase in 2004 on employment among states that indeed raised minimum wage in 2004?

What is the average treatment effect of being eligible for 401(k) retirement plans on asset accumulation?

Notation: Cross-sectional Data

We will adopt the Rubin Causal Model and define potential outcomes.

There are other approaches/languages out there, too, e.g., Judea Pearl’s Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). They should be seen as complements.

Potential outcomes define outcomes in different states of the world, depending on the type of treatment units assigned to them.

Let \(D\) be a treatment variable.

- When \(D\) is binary, \(D_i=1\) means unit \(i\) is treated, and \(D_i=0\) means unit \(i\) is not treated.

- When \(D\) is multi-valued, \(D \in \{0,1,2,\dots,K\}\), \(D_i=d\) means unit \(i\) received treatment \(d\).

- When \(D\) is continuous, \(D \in [a,b]\), \(D_i=d\) means unit \(i\) received treatment \(d\).

Let \(Y_{i}(d)\) be the potential outcome for unit \(i\) if they were assigned treatment \(d\).

Each unit \(i\) has a lot of different potential outcomes

Notation Based on Application About 401(k) Eligibility

What is the average treatment effect of being eligible for 401(k) retirement plans on asset accumulation?

Treatment \(\mathbf{D}:\) \(D_i=1\) if worker \(i\) is eligible for 401(k). \(D_i=0\) if worker \(i\) works in firms that do not offer 401(k).

Potential Outcomes \(\mathbf{Y_i(1)}\), \(\mathbf{Y_i(0)}\) \(Y_i(1)\) asset accumulation for worker \(i\) if eligible for 401(k). \(Y_i(0)\) asset accumulation for worker \(i\) if not eligible for 401(k).

Causality with Potential Outcomes

Unit-specific Treatment Effect

The treatment effect or causal effect of switching treatment from \(d'\) to \(d\) is the difference between these two potential outcomes:

\[ Y_{i}(d) - Y_{i}(d')\]

When treatment is binary, \[ Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0)\]

Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference

Fundamental problem of causal inference (Holland 1986)

- For each unit \(i\), we cannot observe their different potential outcomes at the same time. We only see one of them.

Observed outcome with binary treatments

Observed outcomes for unit \(i\) are realized as \[Y_{i} = 1\{D_i = 1\}Y_{i}(1) + 1\{D_i = 0 \}Y_{i}(0)\]

\[Y_i = \begin{cases} Y_i(1)\text{ if }D_i=1 \\ Y_i(0)\text{ if }D_i=0 \end{cases}\]

Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference: Missing Data Problem

| Unit | \(Y_{i}(1)\) | \(Y_{i}(0)\) | \(D_i\) | \(Y_{i}(1)-Y_{i}(0)\) | \(X_i\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ? | ✓ | 0 | ? | \(x_1\) |

| 2 | ✓ | ? | 1 | ? | \(x_2\) |

| 3 | ? | ✓ | 0 | ? | \(x_3\) |

| 4 | ✓ | ? | 1 | ? | \(x_4\) |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| n | ✓ | ? | 1 | ? | \(x_n\) |

✓: Observed data ?: Missing data (unobserved counterfactuals)

What About Multi-Valued Treatments?

Treatment can take multiple values: \(D_i \in \{0, 1, 2, 3\}\)

- Example: Years of education (0 = no HS, 1 = HS, 2 = Some college, 3 = College+)

- Example: Drug dosage levels (none, low, medium, high)

- Example: Training program intensity

Potential outcomes for each treatment level:

- \(Y_i(0)\), \(Y_i(1)\), \(Y_i(2)\), \(Y_i(3)\) — one for each treatment level

Observed outcome: \[Y_i = \sum_{d=0}^{3} \mathbf{1}\{D_i = d\} \cdot Y_i(d)\]

We observe exactly one of the four potential outcomes

Multi-Valued Treatments: Missing Data Problem

| Unit | \(Y_{i}(0)\) | \(Y_{i}(1)\) | \(Y_{i}(2)\) | \(Y_{i}(3)\) | \(D_i\) | \(X_i\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ✓ | ? | ? | ? | 0 | \(x_1\) |

| 2 | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | 2 | \(x_2\) |

| 3 | ? | ✓ | ? | ? | 1 | \(x_3\) |

| 4 | ? | ? | ? | ✓ | 3 | \(x_4\) |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| n | ? | ? | ✓ | ? | 2 | \(x_n\) |

Key insight: With 4 treatment levels, we observe 1 potential outcome and miss 3 for each unit. The missing data problem is even worse!

What About Continuous Treatments?

Treatment can take any value: \(D_i \in \mathcal{D} \subseteq \mathbb{R}\)

- Example: Hours of training (0 to 2000 hours)

- Example: Tax rate (0% to 100%)

- Example: Class size (10 to 40 students)

- Example: Air pollution level

Potential outcomes for each treatment level:

- \(Y_i(d)\) for every \(d \in \mathcal{D}\) — infinitely many potential outcomes!

Observed outcome: \[Y_i = Y_i(D_i) \quad \text{where } D_i \text{ is the realized treatment}\]

We observe exactly one point on an infinite dose-response curve

Continuous Treatments: The Dose-Response Function

For each unit \(i\):

- The function \(d \mapsto Y_i(d)\) traces out how outcomes vary with treatment dose

- We only observe one point: \((D_i, Y_i(D_i))\)

- The rest of the curve is counterfactual

Causal questions:

- Effect of increasing \(D\) from \(d\) to \(d'\): \(Y_i(d') - Y_i(d)\)

- Marginal effect at dose \(d\): \(\dfrac{\partial Y_i(d)}{\partial d}\)

Key insight: With continuous treatment, we observe 1 point and miss infinitely many. The missing data problem is infinitely worse!

Causality with Potential Outcomes: Even the Simplest Case Is Hard

- Problem:

- Causal inference is difficult because it involves missing data.

- How can we find \(Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0)\)?

- “Cheap” solution - Rule out heterogeneity.

- \(Y_{i}(1), Y_{i}(0)\) constant across units.

- Assuming all potential outcomes are the same is very strong: who believes in that?!

Very little hope for learning about unit-specific treatment effects

We will acknowledge that learning unit-specific TEs is hard, if not impossible.

We will focus on treatment effects in an average sense, but allow them to vary with \(X\).

For simplicity, I will focus on binary treatment setups.

Parameters of Interest: Average Treatment Effects (ATT, ATU)

ATT: The Average Treatment Effect among the Treated units is \[ATT = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) | D_i = 1\right]\]

What is the average treatment effect of being eligible for 401(k) retirement plans on asset accumulation, among workers that are actually eligible for it? Particularly useful to assess if workers that are eligible for 401(k) benefit from it (accumulated more assets).

ATU: The Average Treatment Effect among Untreated units is \[ATU = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) | D_i = 0\right]\]

What is the average treatment effect of being eligible for 401(k) retirement plans on asset accumulation, among workers that were not eligible for it? Particularly useful to assess if 401(k) plan would benefit those who were not eligible for it.

Parameters of Interest: Average Treatment Effects (ATE)

ATE: The (overall) Average Treatment Effect is \[ATE = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0)\right]\]

What is the average treatment effect of being eligible for 401(k) retirement plans on asset accumulation among all workers? Particularly useful to assess the value of 401(k) plans if they were available in all firms.

What if we want to express average causal effects as relative lifts?

Parameters of Interest: Relative Metrics

All the average causal parameters discussed so far are expressed in the same units as \(Y\).

If \(Y\) is expressed in dollars, \(ATE\), \(ATT\) and \(ATU\) will also be expressed in dollars.

If \(Y\) is expressed in number of units shipped, \(ATE\), \(ATT\) and \(ATU\) will also be expressed in number of units shipped.

Sometimes, we want to translate the \(ATE\), \(ATT\) or \(ATU\) into percentage terms.

Parameters of Interest: Relative Treatment Effects

RATT: The Relative Average Treatment Effect among the Treated units is \[RATT = \dfrac{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) | D_i = 1\right]}{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(0) | D_i = 1\right]}\]

RATU: The Relative Average Treatment Effect among Untreated units is \[RATU = \dfrac{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) | D_i = 0\right]}{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(0) | D_i = 0\right]}\]

RATE: The Relative Average Treatment Effect is \[RATE = \dfrac{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0)\right]}{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(0)\right]}\]

What if we want to understand treatment effects in a distributional sense?

Quantile and Distributional Treatment Effects

Despite their popularity, average treatment effects can mask important treatment effect heterogeneity across different subpopulations, see, e.g., Bitler, Gelbach, and Hoynes (2006).

Let’s say that \(ATE\) for being eligible for 401(k) on asset accumulation is $10,000.

- Does eligibility help low-asset households? Is the effect driven by high savers? Does it increase inequality?

We can focus on different treatment effect parameters beyond the mean to better uncover treatment effect heterogeneity. Leading examples include the distributional and quantile treatment effect parameters.

Let \(F_{Y(d)}(y) = \mathbb{P}(Y(d) \le y)\) denote the marginal distribution of the potential outcome \(Y(d)\).

Let \(F_{Y(d)|D=a}(y) = \mathbb{P}(Y(d) \le y|D=a)\) denote the conditional distribution of the potential outcome \(Y(d)\) among units with treatment \(a\).

Distributional Treatment Effects

DTT(y): The Distributional Treatment Effect among the Treated units is \[DTT(y) = F_{Y(1)|D=1}(y) - F_{Y(0)|D=1}(y).\]

DTU(y): The Distributional Treatment Effect among the Untreated units is \[DTU(y) = F_{Y(1)|D=0}(y) - F_{Y(0)|D=0}(y).\]

DTE(y): The Distributional Treatment Effect is \[DTE(y) = F_{Y(1)}(y) - F_{Y(0)}(y).\]

See, e.g., Firpo (2007), Chen, Hong, and Tarozzi (2008), Firpo and Pinto (2016) and Belloni et al. (2017) for discussions.

Computing DTE(y): Illustration

Example: 401(k) eligibility effect on assets (illustrative numbers)

Computing DTE(y): Illustration

Example: 401(k) eligibility effect on assets (illustrative numbers)

Computation at \(y = \$10,000\): \[DTE(\$10k) = F_{Y(1)}(\$10k) - F_{Y(0)}(\$10k) = 0.12 - 0.32 = -0.20\]

Interpretation: 401(k) Eligibility decreases by 20pp the fraction with assets \(\le \$10k\).

Parameters of Interest: Distributional Treatment Effects

All these distributional treatment effect parameters are functional parameters as they vary with the evaluation point \(y\in \mathbb{R}\).

They are all displayed in percentage points, as they are the difference of two distribution functions.

These parameters are bounded between -1 and 1. As a function of \(y\), they all start and end at zero.

Note that if \(y=-\infty\), all of them are zero. If \(y=\infty\), all of them is also zero.

This is equivalent to binarizing the potential outcome using a given threshold, \(\widetilde{Y}_y(d) =1\{Y(d)\leq y\}\), and compute the ATE/ATT/ATU using the binarized outcome.

The appeal is that you do this using many thresholds \(y\), and not only a fixed one.

Parameters of Interest: Distributional Treatment Effects (cont.)

You need to pay attention to the sign of the parameter:

401(k) example: \(DTE(1,000)\) would measure the difference in the fraction of workers with at most $1,000 in accumulated assets in treated and untreated states.

If this number is positive, it means that the fraction of workers accumulating at most $1,000 in assets is higher when they are eligible for 401(k) than if they were not eligible.

This implies that the fraction of workers accumulating more than $1,000 in assets is smaller when they are eligible for 401(k) than if they were not eligible.

Parameters of Interest: Quantile Treatment Effects (Definitions)

For \(\tau\in\left(0,1\right)\), let \(q_{Y(d)}(\tau) = \inf\left\{y:F_{Y(d)}\left(y\right) \geq\tau\right\}\) denote the quantile function of the potential outcome \(Y(d)\).

We define \(q_{Y(d)|D=1}(\tau)\) and \(q_{Y(d)|D=0}(\tau)\) analogously.

These are quantile functions and are always expressed in the same unit of measure as the potential outcome \(Y(d)\).

Parameters of Interest: Quantile Treatment Effects

QTT(\(\tau\)): The Quantile Treatment Effect among the Treated units is \[QTT(\tau) = q_{Y(1)|D=1}(\tau) - q_{Y(0)|D=1}(\tau).\]

QTU(\(\tau\)): The Quantile Treatment Effect among the Untreated units is \[QTU(\tau) = q_{Y(1)|D=0}(\tau) - q_{Y(0)|D=0}(\tau).\]

QTE(\(\tau\)): The Quantile Treatment Effect is \[QTE(\tau) = q_{Y(1)}(\tau) - q_{Y(0)}(\tau)\]

E.g., if \(QTE(\tau) \approx \$0\) for \(\tau \in (0,0.3)\), \(QTE(\tau) \approx \$5,000\) for \(\tau \in (0.4,0.6)\), and \(QTE(\tau) > \$15,000\) for \(\tau > 0.7\), this would mean that 401(k) eligibility benefits mostly those in the upper-tail of the wealth distribution.

Computing QTE(\(\tau\)): Same CDFs, Different Perspective

Key insight: QTE fixes a probability (quantile \(\tau\)) and compares asset levels

Computing QTE(\(\tau\)): Illustration

Example: 401(k) eligibility effect on assets (same distributions as before)

Computing QTE(\(\tau\)): Illustration

Example: 401(k) eligibility effect on assets (same distributions as before)

Computation at \(\tau = 0.5\) (median): \[QTE(0.5) = q_{Y(1)}(0.5) - q_{Y(0)}(0.5) = \$35k - \$24k = \$11k\]

Interpretation: Eligibility increases median assets by $11,000.

Distribution and Quantile of the Treatment Effects

The quantile and distributional treatment parameters discussed up to now are expressed as the difference of two quantile and distribution functions, respectively.

In general, these should not be interpreted as the distribution of the treatment effects, or the quantile of the treatment effects; see, e.g., Heckman, Smith, and Clements (1997), Masten and Poirier (2020), and Callaway (2021).

They can sometimes coincide, but that requires additional assumptions, such as rank-invariance; see, e.g., Heckman, Smith, and Clements (1997) for a discussion.

Distribution and Quantile of the Treatment Effects (cont.)

DoTT(y): The Distribution of Treatment Effect among the Treated units is \[DoTT(y) = F_{Y(1)-Y(0)|D=1}(y).\]

DoTE(y): The Distribution of Treatment Effect \[DoTE(y) = F_{Y(1)-Y(0)}(y).\]

QoTT(\(\tau\)): The Quantile of Treatment Effect among the Treated units is \[QoTT(\tau) = q_{Y(1)-Y(0)|D=1}(\tau).\]

QoTE(\(\tau\)): The Quantile of Treatment Effect is \[QoTE(\tau) = q_{Y(1)-Y(0)}(\tau).\]

Computing DoTE(y): Illustration

Example: Distribution of treatment effects for 401(k) eligibility

Computing DoTE(y): Illustration

Example: Distribution of treatment effects for 401(k) eligibility

Computation at \(y = \$10,000\): \[DoTE(\$10k) = F_{Y(1)-Y(0)}(\$10k) = 0.50\]

Interpretation: 50% of the population has treatment effects \(\le \$10,000\).

Computing QoTE(\(\tau\)): Same CDF, Different Perspective

Key insight: QoTE fixes a probability (quantile \(\tau\)) and finds treatment effect value

What if we want to understand how the average causal effects vary with covariates?

Parameters of Interest: Conditional Average Treatment Effects

Let \(X_{all}\) be a set of features/covariates available to you, and let \(X_{s}\) be a subset of \(X_{all}\).

CATE: The Conditional Average Treatment Effect given \(X_{sub}\) is \[CATE_{X_{s}}(x_{s}) = \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1) - Y_{i}(0) | X_{s} = x_{s}\right]\]

How does the average treatment effect of being eligible for 401(k) retirement plans on asset accumulation vary with age, marital status, and number of kids? What about education?

Note that CATE\((x_s)\) is a functional parameter, as it varies with the covariate values \(x_s\).

Other parameters have similar characterizations.

Computing CATE(age): Illustration

Example: How does 401(k) eligibility effect vary with age?

Computing CATE(age): Illustration

Example: How does 401(k) eligibility effect vary with age?

Computations at different ages:

- CATE(25) = $5k: Young workers gain $5,000 in assets

- CATE(40) = $15k: Mid-career workers gain $15,000

- CATE(55) = $27k: Older workers gain $27,000

Interpretation: Older workers benefit more from 401(k) eligibility, possibly due to higher earnings and greater ability to contribute.

There Is No

“The” Causal Effect!

Only different averages, distributions, and quantiles

There Is No “The” Causal Effect

Unit-specific effects \(Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)\) vary across units

- Treatment effect heterogeneity is the norm, not the exception

When we report “the ATT” or “the ATE,” we’re reporting one particular average

Different parameters answer different questions:

- ATT, ATE, CATE: Different averages across units

- DTE, QTE, DoTE: Distributional summaries of effects

Key Insight: The “right” parameters are ones that are meaningful for your research question. More complex parameters can reveal richer heterogeneity, but may also be harder to learn.

All these are very well motivated in cross-sectional setups.

But what if we have panel data?

Do we need to adapt these different parameters?

Why Standard Potential Outcomes Fall Short

Consider these counterfactual questions:

- Medicaid Expansion: “What would mortality be if a state expanded in 2014 vs. 2019 vs. never?”

- \(Y(0)/Y(1)\) can’t distinguish when treatment occurred

- Divorce Laws: “What is the effect 1 year vs. 5 years vs. 10 years after adoption?”

- Simple \(Y(0)/Y(1)\) can’t capture dynamic effects over time

- Democracy & Growth: “What is GDP if always democratic vs. democratized then reverted vs. never democratic?”

- \(Y(0)/Y(1)\) can’t capture treatment history

Takeaway: We need potential outcomes indexed by treatment histories, not just current treatment status

Potential Outcomes and Causal Parameters with Panel Data

Different Treatment Settings in Panel Data

- Same underlying framework, but how do we define “groups”?

Defining Treatment Groups

- Single treatment time: Group = treated vs. never-treated

- Staggered: Group = first treatment period \(G_i\)

- On/Off: Group = unique treatment sequence \(\Rightarrow\) more groups, more parameters!

Single Treatment Time: The Simplest Case

Setting:

- All treated units start treatment at the same time \(g\)

- Treatment never turns off

- Some units never treated (\(G_i = \infty\))

Example: Card and Krueger (1994)

- NJ raises minimum wage in April 1992

- PA does not (control group)

- Two periods: before and after

Only two treatment sequences matter:

- Treated: \(\mathbf{d} = (0,\ldots,0,1,\ldots,1)\) starting at \(g\)

- Never-treated: \(\mathbf{d} = (0,0,\ldots,0)\)

Single Treatment Time: Simplified Notation

With a single treatment time, we can simplify:

- Index potential outcomes by whether treated, not full sequence

- \(Y_{it}(g)\) = outcome if first treated at \(g\) (and treatment stays on)

- \(Y_{it}(\infty)\) = outcome if never treated

This maps to our cross-sectional notation:

- \(Y_{it}(g) \approx Y_{it}(1)\) (treated potential outcome at time \(t\))

- \(Y_{it}(\infty) \approx Y_{it}(0)\) (untreated potential outcome at time \(t\))

Key insight: All parameters from earlier apply, but now indexed by time: \(ATT(t) = \mathbb{E}[Y_{it}(g) - Y_{it}(\infty) \mid G_i = g]\).

Can study dynamic effects: How does \(ATT(t)\) change as \(t\) increases?

Beyond \(ATT(t)\): Other Parameters of Interest

Remember our cross-sectional parameters? They all extend to panel data!

ATE\((t)\) \(= \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(\infty)]\) - Effect if everyone were treated at \(g\) vs. never

QTT\((t,\tau)\) \(= q_{Y_t(g)|G=g}(\tau) - q_{Y_t(\infty)|G=g}(\tau)\) - Effect at \(\tau\)-th quantile for the treated at time \(t\)

DTT\((t,y)\) \(= F_{Y_t(g)|G=g}(y) - F_{Y_t(\infty)|G=g}(y)\) - Distributional effects: How does the CDF shift?

DoTT\((t,y)\) \(= F_{Y_t(g)-Y_t(\infty)|G=g}(y)\) - Full distribution of unit-level effects

CATT\((t,x)\) \(= \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(\infty) | G=g, X=x]\) - Heterogeneous effects by pre-treatment covariates

Key insight: Panel data enriches all parameters with time dimension \(t\). Each requires additional assumptions and estimation strategies.

Single Treatment Time: Aggregating Over Time

With multiple post-treatment periods, we have many \(ATT(t)\)’s:

| \(t=1\) | \(t=2\) | \(t=3\) | \(t=4\) | \(t=5\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(g=3\) | — | — | \(ATT(3)\) | \(ATT(4)\) | \(ATT(5)\) |

Summary measures:

- Overall ATT: \(\displaystyle ATT = \frac{1}{T-g+1} \sum_{t=g}^{T} ATT(t)\)

- Simple average across all post-treatment periods

- Other weighting schemes: \(\displaystyle ATT_w = \sum_{t=g}^{T} w_t ATT(t)\)

- Choose weights \(w_t\) based on importance

- Allows discounting distant periods more heavily

- E.g., \(w_t \propto \rho^{t-g}\) for some \(\rho \in (0,1)\)

Staggered Adoption: Multiple Treatment Cohorts

Setting:

- Units start treatment at different times

- Once treated, treatment never turns off

- \(G_i \in \{2, 4, 6, \infty\}\)

Some Empirical Examples:

- Medicaid: States expanded in 2014, 2015, …, or never (Miller, Johnson, and Wherry 2021)

- Divorce laws: States adopted unilateral divorce at different times (Wolfers 2006)

Treatment sequence determined by \(G_i\):

- \(G_i = 2\): \((0,1,1,\ldots)\) | \(G_i = 4\): \((0,0,0,1,\ldots)\) | \(G_i = 6\): \((0,0,0,0,0,1,\ldots)\) | \(G_i = \infty\): \((0,0,\ldots)\)

Staggered Adoption: Group-Time ATT

Since treatment stays on, potential outcomes indexed by first treatment time:

- \(Y_{it}(g)\) = outcome for unit \(i\) at time \(t\) if first treated at \(g\)

- \(Y_{it}(\infty)\) = outcome if never treated

- Observed: \(Y_{it} = \sum_{g \in \mathcal{G}} \mathbf{1}\{G_i = g\} Y_{it}(g)\)

Group-time ATT (Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021): \[ATT(g, t) = \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(\infty) \mid G = g]\]

- Effect for units first treated at \(g\), measured at time \(t\)

- Allows heterogeneity across cohorts and time

Building blocks: The \(ATT(g,t)\)’s are fundamental parameters. We can aggregate them in different ways to answer different research questions.

Staggered Adoption: Many Parameters!

Example: \(T = 5\) periods, groups \(g \in \{2, 3, 4, 5, \infty\}\)

| \(t=2\) | \(t=3\) | \(t=4\) | \(t=5\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(g=2\) | \(ATT(2,2)\) | \(ATT(2,3)\) | \(ATT(2,4)\) | \(ATT(2,5)\) |

| \(g=3\) | — | \(ATT(3,3)\) | \(ATT(3,4)\) | \(ATT(3,5)\) |

| \(g=4\) | — | — | \(ATT(4,4)\) | \(ATT(4,5)\) |

| \(g=5\) | — | — | — | \(ATT(5,5)\) |

10 parameters! And this is just 5 periods…

- Hard to estimate each precisely

- Hard to interpret/communicate

- Need to aggregate into summary measures

Question: Which aggregation should you use? It depends on your research question!

Aggregation Strategies: Roadmap

We have many \(ATT(g,t)\) parameters. How do we aggregate them?

Four main approaches, each answering a different question:

Cohort Heterogeneity \(\theta_S(g)\) “How does the average effect differ for early vs. late adopters?”

Calendar Time \(\theta_C(t)\) “What is the overall policy average effect at time \(t\)?”

Event-Study \(\theta_D(e)\) “How do average effects evolve with exposure (e.g., 1 year post, 2 years post)?”

Overall Average \(\theta^O\) “What is a single summary number for the entire policy?”

Key insight: All four are valid! Your choice depends on your research question.

Aggregating \(ATT(g,t)\): Weighted Averages

General form: \(\displaystyle\sum_{g=2}^{T} \sum_{t=2}^{T} \mathbf{1}\{g \leq t\} \, w_{g,t} \, ATT(g,t)\)

Simple aggregations (assuming no-anticipation):

Unweighted average: \[\theta_M^O := \frac{2}{T(T-1)} \sum_{g,t: g \leq t} ATT(g,t)\]

Weighted by group size: \[\theta_W^O := \frac{1}{\kappa} \sum_{g,t: g \leq t} ATT(g,t) \cdot P(G = g | G \neq \infty)\]

Problem: These “overweight” units that have been treated longer (early adopters contribute more)!

Aggregation Strategy 1:

Cohort Heterogeneity

Focus: Do early vs. late adopters experience different average effects?

Aggregating \(ATT(g,t)\): Cohort Heterogeneity

Average effect for units in group \(g\):

\[\theta_S(g) = \frac{1}{T - g + 1} \sum_{t=g}^{T} ATT(g,t)\]

- Averages across row for cohort \(g\)

- Shows heterogeneity across cohorts

- Early vs. late adopters may differ

Question: “Do early Medicaid expanders benefit more than late expanders?”

Aggregation Strategy 2:

Calendar Time Heterogeneity

Focus: What is the overall average effect at a specific calendar time?

Aggregating \(ATT(g,t)\): Calendar Time Heterogeneity

Average effect at time \(t\) for all treated:

\[\theta_C(t) = \sum_{g \leq t} ATT(g,t) \cdot P(G = g | G \leq t)\]

- Averages down column at time \(t\)

- Useful when calendar time matters

- Weights by group size

Question: “What was the overall policy average impact among treated in 2020?”

Aggregation Strategy 3:

Event-Study / Dynamic Effects

Focus: How do average effects evolve with time since treatment?

Aggregating \(ATT(g,t)\): Event-Study / Dynamic Effects

Average effect at exposure \(e = t - g\):

\[\theta_D(e) = \sum_{g: g+e \leq T} ATT(g, g+e) \cdot P(G = g | G+e \leq T)\]

- Averages along diagonal (same \(e\))

- Weights = group sizes (cohort shares)

- \(e = 0\): on impact; \(e = 1,2,\ldots\): dynamics

Question: “How does the effect evolve since adoption?” (Wolfers 2006)

Event-Study Plots: How Results Are Typically Presented

Event-study aggregations \(\theta_D(e)\) are plotted against event time \(e = t - g\):

- \(e < 0\): Pre-treatment periods

- \(e = 0\): Treatment onset

- \(e > 0\): Post-treatment periods

Typical features:

- Confidence intervals shown

- Reference line at zero

- Pre-trends visible for \(e < 0\)

Questions: Why are these pre-treatment parameters zero? Do they need to be zero?

Aggregation Strategy 4:

Overall Summary (Scalar)

Focus: What is one single number summarizing the entire policy effect?

Overall Summary Parameters: Scalar Aggregations

Sometimes we want a single number! Further aggregate the intermediate parameters:

- Overall cohort effect: \(\theta^O_S = \sum_{g=2}^{T} \theta_S(g) \cdot P(G = g | G \neq \infty)\) (weighted avg)

- Overall calendar-time effect: \(\theta^O_C = \frac{1}{T-1} \sum_{t=2}^{T} \theta_C(t)\) (simple avg)

- Overall event-time effect: \(\theta^O_D = \frac{1}{T-1} \sum_{e=0}^{T-2} \theta_D(e)\) (simple avg)

Key insight: \(\theta^O_S\), \(\theta^O_C\), and \(\theta^O_D\) need not be equal! But we know how they relate via \(ATT(g,t)\).

Which to report? Depends on your research question:

- Policy evaluation at specific time → \(\theta_C(t)\) or \(\theta^O_C\)

- Early vs. late adopters → \(\theta_S(g)\) or \(\theta^O_S\)

- Dynamic effects → \(\theta_D(e)\) or \(\theta^O_D\)

Aggregation Strategies: Summary Reference

Key Insight: All four are valid! They answer different questions. Choose based on whether you care about: (1) which groups, (2) which time periods, (3) dynamics, or (4) overall summary.

Are \(ATT(g,t)\)’s the Only Building Blocks?

Question for you:

Is \(ATT(g,t) = \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(\infty) | G = g]\) the only causal parameter we can define?

Obviously not! Remember our cross-sectional parameters? They all extend to \((g,t)\):

- \(QTT(g,t,\tau)\) — Quantile effects for cohort \(g\) at time \(t\)

- \(DTT(g,t,y)\) — Distributional effects

- \(CATT(g,t,x)\) — Heterogeneous effects by covariates

The \(ATT(g,t)\) framework is a template — swap in your parameter of interest!

Beyond \(ATT(g,t)\): Other Target Populations

\(ATT(g,t)\) always conditions on \(G = g\). But we can target other populations:

ATU\((g,t)\) — Effect for the never-treated: \[ATU(g,t) = \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(\infty) \mid G = \infty]\]

ATE\((g,t)\) — Effect for everyone: \[ATE(g,t) = \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(\infty)]\]

Key point: All compare treatment at \(g\) vs. never-treated (\(\infty\)). But who are we averaging over? Treated (\(G=g\)), never-treated (\(G=\infty\)), or everyone?

Beyond \(ATT(g,t)\): Different Baselines

Why always compare to never-treated? We can compare different treatment timings:

- ATT\((g', g, t \mid g^*)\) — Effect of switching from \(g'\) to \(g\), for group \(g^*\): \[ATT(g', g, t \mid g^*) = \mathbb{E}[Y_t(g) - Y_t(g') \mid G = g^*]\]

Example: What’s the effect of adopting Medicaid in 2014 vs. 2016?

- Compare \(Y_t(g=2014)\) vs. \(Y_t(g'=2016)\), not vs. \(Y_t(\infty)\)

- This captures the value of earlier vs. later adoption

Takeaway: The potential outcomes framework is flexible! Define the comparison that answers your research question.

What Have We Assumed So Far?

A hidden assumption in everything we’ve done:

Once treated, always treated.

(Treatment is absorbing)

Staggered adoption allows:

- \((0,0,0,0)\) — Never treated

- \((0,0,1,1)\) — Adopt in period 3

- \((0,1,1,1)\) — Adopt in period 2

- \((1,1,1,1)\) — Always treated

Staggered adoption forbids:

- \((0,1,0,0)\) — Treatment ends

- \((0,1,0,1)\) — On-off-on

- \((1,0,1,0)\) — Alternating

- Any sequence with \(D_t > D_{t+1}\)

But What If Treatment Can Turn Off?

Many real-world treatments are not absorbing:

Democracy — Countries democratize and experience reversals (Acemoglu et al. 2019)

Policy adoption — States adopt minimum wages, then repeal them

Program participation — Workers enter and exit job training

Medical treatments — Patients start and stop medications

The question: How do we define potential outcomes and causal parameters when treatment sequences can be any pattern of 0s and 1s?

The General Framework: Treatment Sequences (Robins 1986)

Single treatment time and Staggered are special cases of a more general setup:

Let \(D_{it} \in \{0,1\}\) be treatment status for unit \(i\) at time \(t\)

Treatment sequence: \(\mathbf{d} = (d_1, d_2, \ldots, d_T)\) where each \(d_t \in \{0,1\}\)

Examples with \(T=4\):

- \(\mathbf{d} = (0,0,0,0)\): Never treated \(\Rightarrow G_i = \infty\)

- \(\mathbf{d} = (0,1,1,1)\): Treated starting period 2 \(\Rightarrow G_i = 2\) (staggered)

- \(\mathbf{d} = (0,1,0,0)\): Treated period 2 only, then off

- \(\mathbf{d} = (0,1,0,1)\): On, off, on again

Single treatment time: Only \((0,\ldots,0,1,\ldots,1)\) at fixed \(g\) or \((0,\ldots,0)\)

Staggered: Only \((0,\ldots,0,1,\ldots,1)\) at varying \(g\) or \((0,\ldots,0)\)

General: Any sequence \(\mathbf{d} \in \{0,1\}^T\)

Potential Outcomes with Treatment Sequences

General notation (encompasses Single treatment time and Staggered):

- \(Y_{it}(\mathbf{d})\) = potential outcome for unit \(i\) at time \(t\) under sequence \(\mathbf{d}\)

- Never-treated: \(Y_{it}(\infty) = Y_{it}(0,0,\ldots,0)\)

- Observed outcome: \(Y_{it} = \sum_{\mathbf{d} \in \mathcal{D}} \mathbf{1}\{G_i = \mathbf{d}\} Y_{it}(\mathbf{d})\)

How our earlier notation fits:

- Single time/Staggered: \(Y_{it}(g) = Y_{it}(\underbrace{0,\ldots,0}_{g-1},\underbrace{1,\ldots,1}_{T-g+1})\)

- The \(g\)-notation is shorthand when treatment never turns off!

Key insight: Robins notation handles ALL cases—Single treatment time and Staggered are special cases where sequences have a simple structure.

The General Building Block: \(ATT(\mathbf{d}, t)\)

Building Block causal parameter: \(ATT(\mathbf{d}, t) = \mathbb{E}[Y_t(\mathbf{d}) - Y_t(\infty) \mid G = \mathbf{d}]\)

- Effect of sequence \(\mathbf{d}\) vs. never-treated | Among units that actually followed sequence \(\mathbf{d}\) | At time \(t\)

Connection to what we learned:

- Single treatment time: \(ATT(\mathbf{d}, t) \to ATT(t)\) (one treated group)

- Staggered: \(ATT(\mathbf{d}, t) \to ATT(g,t)\) (groups indexed by \(g\))

- General: \(ATT(\mathbf{d}, t)\) for each unique sequence \(\mathbf{d}\)

With \(T\) periods: up to \(2^{T-1}\) potential treatment sequences! Not all need to exist, i.e., some \(\mathbf{d}\) may have zero probability.

Most General Case: Treatment Can Turn On and Off

When treatment can turn on AND off:

- Full sequence \(\mathbf{d} = (d_1, \ldots, d_T)\) may matter

- We cannot simplify to just “when first treated” (\(G^{start}\))

- Doing so can hide important treatment effect heterogeneity

Example: Democracy & Growth (Acemoglu et al. 2019)

- Countries can democratize and revert to autocracy

- Different sequences have different meanings:

- \((0,1,1,1)\): Stable democracy since period 2

- \((0,1,0,0)\): Brief democratic episode, then reversal

- \((0,1,0,1)\): Democratize, revert, re-democratize

- These may have very different effects on GDP!

Visualizing Treatment On/Off: Democracy Example

Same \(G^{start}\), very different histories! Grouping by “when first treated” lumps together stable democracies, brief episodes, and on-off patterns. (Illustrative example)

The Explosion of Parameters

With \(T\) periods (no one treated in \(t=1\)): \(2^{T-1}\) possible treatment sequences

Example with \(T=4\):

Staggered adoption:

- 3 treated groups: \(G \in \{2,3,4\}\)

- 6 post-treatment \((g,t)\) pairs

- \(\Rightarrow\) 6 parameters

Treatment on/off:

- 7 treated sequences

- 17 post-treatment \((\mathbf{d},t)\) pairs

- \(\Rightarrow\) 17 parameters!

The practical challenge:

- Estimating 17+ parameters with precision is hard

- Communicating treatment effect heterogeneity across sequences is even harder

- Natural instinct: aggregate — but how?

Aggregation Challenge: What Does “Event-Study” Mean?

Common approach: Aggregate by “time since first treated” (\(e = t - g^{start}\))

Define \(\widetilde{ATT}(g^{start}, t)\) = weighted average of \(ATT(\mathbf{d}, t)\) across all sequences \(\mathbf{d}\) that start treatment at \(g^{start}\).

Democracy example: What does \(\widetilde{ATT}(g^{start}=2, t=4)\) aggregate?

- \((0,1,1,1)\): Stable democracy for 3 periods

- \((0,1,1,0)\): Democratic for 2 periods, then reverted

- \((0,1,0,0)\): Democratic for 1 period only

- \((0,1,0,1)\): Democratic, reverted, re-democratized

The interpretation problem: \(\widetilde{ATT}(g^{start}, t)\) mixes units with very different treatment histories! At \(t=4\), some countries had 3 years of democracy, others had 1, others had 2 with a gap.

This is hard to rationalize if democratization affects GDP not only contemporaneously but also via duration and persistence, i.e, in the presence of carryover effects.

Event-Study Aggregation: \(\widetilde{\theta}_D(e)\)

Several papers discuss “staggerizing” treatment using \(G^{start}\) (Sun and Abraham 2021; Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille 2024): \[\widetilde{\theta}_D(e) = \sum_{g^{start}} w(g^{start}; e) \cdot \widetilde{ATT}(g^{start}, g^{start} + e)\] where \(w(g^{start}; e) = P(G^{start} = g^{start} \mid G^{start} + e \leq T)\) is the cohort share among units first-treated at least \(e\) periods ago.

Unfortunately, \(\widetilde{\theta}_D(e)\) does NOT represent an average effect w.r.t. length of exposure.

Why not?

- We aggregate across treatment paths with different exposure patterns

- At “\(e=2\)”, some units were treated twice, others only once

- “Event time” \(e\) doesn’t correspond to actual treatment duration!

Democracy: “2 years since first democratized” includes stable democracies AND countries that reverted.

Comparing Event-Studies: Staggered vs. On/Off

Staggered Adoption

✓ Clear interpretation: \(e=2\) means 2 periods of treatment

Treatment On/Off

✗ Unclear interpretation: \(e=2\) mixes different exposures

With treatment on/off, event-study coefficients aggregate incomparable treatment histories.

What Can We Do?

Several papers discuss potential ways to move forward in this setting (Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille 2020, 2024; Liu, Wang, and Xu 2024)

These solutions often involve restricting treatment effect dynamics by imposing limited/no-carryover conditions:

- No-carryover: \(Y_{it}(\mathbf{d}) = Y_{it}(d_t)\) — only current treatment matters

- Limited carryover: \(Y_{it}(\mathbf{d}) = Y_{it}(d_{t-L}, \ldots, d_t)\) — only recent \(L\) periods matter

These assumptions rule out long-run treatment effect dynamics

Key insight: The Robins (1986) framework handles treatment on/off, but aggregation and interpretation become much harder without restricting how past treatments affect current outcomes.

Beyond Binary Treatments

Beyond Binary Treatments

Everything discussed generalizes to multi-valued and continuous treatments

In staggered adoption, potential outcomes indexed by \((g, d)\):

- \(g\) = when treatment starts; \(d\) = dosage/intensity

The potential outcomes framework extends naturally:

- Binary: \(Y_{it}(g,d)\) with \(d \in \{0, 1\}\)

- Multi-valued: \(Y_{it}(g, d)\) with \(d \in \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\}\)

- Continuous: \(Y_{it}(g, d)\) with \(d \in \mathcal{D} \subseteq \mathbb{R}\)

Same principles for causal parameters and aggregations apply

See Callaway, Goodman-Bacon, and Sant’Anna (2024) for details

Example: Minimum Wage and Employment

Setting: States adopt different minimum wage levels at different times

Causal parameters: \(ATT(g, d, t)\) — effect of adopting wage \(d\) at time \(g\), measured at \(t\)

- Compare \(Y_{it}(g, d)\) vs. \(Y_{it}(\infty)\) (federal minimum baseline)

- Same \(g\), different \(d\) (A vs. B) \(\Rightarrow\) dose-response (Illustrative)

Summary

Summary: Key Takeaways

Potential outcomes provide a unified framework for defining causal effects in panel data

Treatment timing matters: Single treatment time \(\to\) Staggered adoption \(\to\) Treatment on/off

Building blocks: \(ATT(g,t)\) parameters capture group-time specific effects

Aggregation: Cohort \(\theta_S(g)\), calendar time \(\theta_C(t)\), and event-study \(\theta_D(e)\) answer different questions

Flexibility vs. tractability: More general treatment patterns are hard to learn and aggregate absent additional assumptions (e.g., limited/no-carryover)

The framework is a template: Extends to QTT, DTT, CATT, ATU, ATE, and continuous treatments

Decision Guide: What’s Your Treatment Pattern?

Start with your empirical setting, then choose the appropriate framework!

Suggested Exercise

Suggested Exercise

Choose an empirical panel data paper and analyze its causal framework:

What is the treatment? Is it binary, multi-valued, or continuous?

What treatment pattern applies? Single treatment time, staggered adoption, or on/off?

What are the potential outcomes? Write them out explicitly.

What causal parameter is the paper targeting? \(ATT(g,t)\)? An aggregation?

Could the paper benefit from alternative parameters (e.g., event-study, heterogeneity by covariates)?

This exercise builds intuition for connecting empirical questions to the potential outcomes framework.

Questions?

Next: Randomizing Treatment Sequences

References

ECON 730 | Causal Panel Data | Pedro H. C. Sant’Anna